Welcome to Book of the Week – a weekly feature of an Acres U.S.A. published title offering you a glimpse between the pages! Get the Book of the Week email newsletter delivered directly to your inbox!

This week’s Book of the Week feature is The Farm as Ecosystem, by Jerry Brunetti.

Add The Farm as Ecosystem to my cart.

From Chapter 6: Foliar Nutrition

The idea of feeding plants nutritional ingredients is hardly a new one, and mixed results have rendered it a controversial methodology. The key to consistent outcomes is predicated on a number of ground rules, which if adhered to can provide remarkable responses in any crop.

The uptake of nutrition via foliage can be ten to twenty times more efficient than what plants can take in the root. However, soil amendments and soil-applied plant foods are needed to not only feed the plant but also support the entire soil ecosystem of the plant.

There are five primary advantages to foliar feeding.

- Rapid and efficient uptake of nutrients.

- Provides nutrients in problem soils where there is limited biology, which inhibits the uptake of soil nutrients into the plant. Examples are compacted soil, waterlogged soil nutrients, or excess leaching of soil nutrients (sandy soils).

- Minimizes the stress of weather extremes (drought, cold, wet, cloudy weather).

- Incites induced activated resistance (IAR), which is a grower’s way of stimulating a protective response similar to what a healthy plant does when challenged by a pest, which is called systemic acquired resistance (SAR). Plants under attack release compounds called phytoalexins, which perform as deterrents or toxins to adversarial challenges.

- Manipulates the metabolism of plants so that the growth or vegetative phase can be morphed into a reproductive phase, where fruit or seed is desired.

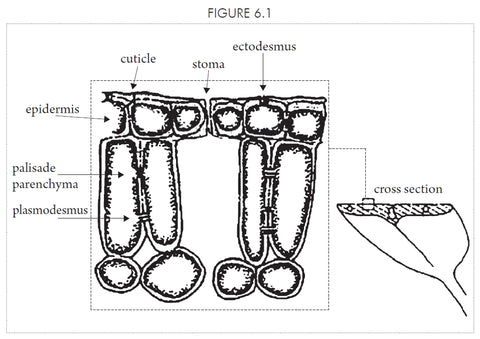

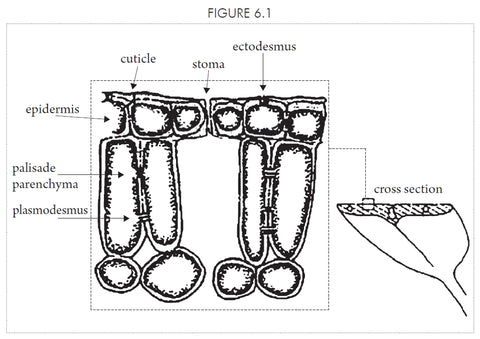

As one can see from the figure 6.1, there are a number of portals for foliar substances to enter the cytoplasm of a leaf’s cell. The cuticle is a waxy layer covering the leaves, and its primary function is to prevent moisture loss and plant tissue injury. The cuticle is a triple-layer covering consisting of cutin—the lowest or first layer—covered by a wax layer in the middle, covered by a wax rodlet on top. Cracks in the cuticle occur and can serve as a port of entry for foliar sprays. The stomata are located almost exclusively on leaves and are only a few millionths of an inch in diameter. They are breathing holes, allowing CO2 gas to enter so that plants can photosynthesize it into sugar in the chloroplast while emitting oxygen into the atmosphere. They are also thermo-regulators allowing a plant to transpire, that is, getting rid of water vapor to cool the plant. The stomata are closed at night and the hottest part of the day. Broadleaf plants and trees have the vast majority of their stomata on the bottom of the leaf. Grasses can have the same number of stomata on both surfaces. For example, a bean plant can have 40,000 stomata on the underside of the leaf and only 3,000 on the upper side, while a sorghum plant can have 16,000 on the lower surface and 11,000 on top. Also, grass stomata can be several times the diameter of dicots/broadleaf stomata. Because younger plants have so much thinner a cuticle than older plants, they readily respond to foliar feeding as they are much more efficient in absorbing nutrients.

Foliar nutrients have to be in an ionic or colloidal presentation in order for plants to be able to take in the nutrients. An example of an anionic solution is salt water; an example of a colloidal liquid is whole, homogenized milk. Some foliar products may be finely ground rock materials but are still too large. Particle size matters! Most growers are unaware that the uptake and utilization of foliars is quite inefficient because of the difficulty the applied substance has penetrating the waxy cuticle. That may mean that only 10–20 percent of nutrients applied are taken in, the remaining being washed off into the soil. Particle sizes are usually measured in microns, 0.001 meter or 0.00004 inch. Many commercial products may average forty to fifty microns, quite small if it gets into the soil, but the leaf stoma are only five microns. Five pounds of a fifty-micron product has a surface area of about seven hundred square feet. The same amount at one micron has a surface area of 27,000 square feet! Entry points for foliar-applied materials are the stomata, the ectodesmus, and the cuticle, with the cuticle offering the largest surface area but the smallest entry point into the vascular organs in the plant. Also, many of these micronized compounds are complex compounds such as carbonates (limestone) and phosphates (tri-calcium phosphates like rock phosphate), which are not likely to be assimilated and transported throughout the plant’s vascular system because substances that enhance movement within the plant are usually ion specific. Their advantage would be in a soil drench/fertigation system to be assimilated more efficiently by the roots.

As the old adage states, “Timing is everything.” As it pertains to foliar application, timing is not only important, it can be critical. Early morning or dusk are the opportune times to apply foliars because the stomata are more likely to be open when temperatures are lower, humidity is high, and dew is on the leaves. Ideally, temperatures below 80°F are preferred. In midday, hot temperatures will cause the stomata to close off to entry of even carbon dioxide gas, which is necessary for photosynthesis. Apparently, higher temperatures increase carbon dioxide concentrations inside the leaf, which acts as a trigger to close the stomata. For every 10°C (50°F) increase in temperature, the rate of water evaporation doubles. Stomata actually close when air temperatures exceed 85°F, and plants give up moisture above those temperatures through a process called transpiration. Also, elevated temperatures remove the water carrying the nutrients, which allows the nutrients to stay in a water capsule until the plant is ready to take them in.

It isn’t a good idea to foliar spray when too cool (less than 50°F), either, because plant physiological functions are not optimum. Don’t spray the same day rain is forecast, as the combination of precipitation (runoff) and cloudy weather (compromised photosynthesis) is objectionable to the goal of foliar feeding: leaf absorption. The intervals in the crop growth cycle are also important. Typically, for row crops and produce, foliars should be applied at the third to sixth or seventh leaf stage, as young plant tissue is quite responsive because it needs to synthesize those protective plant secondary metabolites. And another spray could be done ten to fourteen days later.

For high-value crops such as produce, fruit, berries, vines, and brambles, a schedule of every ten to fourteen days throughout the season until harvest can produce gratifying dividends. For those high-value crops, petiole and tissue tests throughout the season, as recommended by the standards set within the industry, are a good idea. For forage and row crops (cereals, corn, beans), at least one and preferably two sprays would be recommended. Established tissue guidelines are typically utilized to find the ranges of elements within the variety of crop. What is typically seen is that as the plant matures and therefore creates more biomass, the desired nutrient levels in percentages or parts per million decline. Early sampling can be important because some crops like cereals, forages, and corn determine the number of ears, pods, grain, and seed at early growth phases; for example corn determines the number of ears it will produce at the fifth or sixth collar stage. Essentially, the tissue test is the report card for your soil test. To have a stronger hand on the pulse of your growing endeavor, you need “real time” information to ascertain if what’s in the soil is manifesting in your crop, and if not, how to make adjustments.

Learn more about The Farm as Ecosystem here.

Add The Farm as Ecosystem to my cart.

About the Author:

Jerry Brunetti,1950-2014, worked as a soil and crop consultant, primarily for livestock farms and ranches, and improved crop quality and livestock performance and health on certified organic farms. In 1979, he founded Agri-Dynamics Inc., and confounded Earthworks in 1990. He spoke widely on the topics of human, animal and farm health.

More From this Author:

Jerry Brunetti Workshop Lectures Complete Set on USB Thumbdrive

Cancer, Nutrition, and Healing DVD

Similar Books of Interest:

Secrets of Fertile Soils, by Erhad Hennig

The Art of Balancing Soil Nutrients, by William McKibben

From the Soil Up, by Donald Schriefer

More Book of the Week Excerpts:

Hands-On Agronomy – Chapter 14 – by Neal Kinsey

In the Shadow of Green Man – Chapter 1 – by Reginaldo Haslett-Marroquín

Albrecht on Soil Balancing, Vol. II – Chapter 17 – by William A. Albrecht