Welcome to Book of the Week – a weekly feature of an Acres U.S.A. published title offering you a glimpse between the pages! Get the Book of the Week email newsletter delivered directly to your inbox!

This week’s Book of the Week feature is Fertility Farming, by Newman Turner.

Add Fertility Farming to my cart.

From Chapter Seventeen: Pigs and Poultry on the Fertility Farm

In the building up of fertility, especially on the poor light-land farm, there is no animal more effective than the pig. Though I would not suggest that the pig is an essential part of fertility building, there is no quicker or more economical contributor to soil fertility. There is, consequently, a strong case for keeping pigs on the farm of low fertility for no other reason than that of fertility making, quite apart from any direct profits which may accrue. I kept pigs in the early days at Goosegreen and have used them in large numbers for land reclamation work which I have directed elsewhere. The system used, which has already been copied with success in a number of land reclamation schemes, was originated by my mother and brothers (M. E. Turner & Sons, Brockholes Farm, Branton, Doncaster), with their large pedigree Essex herd, before the war.

In the 1930s they took over one of the poorest blow-away sand-land farms in South Yorkshire, which was already known as incapable of growing anything without large quantities of artificial fertilizer, and because of the difficult times through which farming was passing, few farmers had the means to risk the immense cost of artificial fertilizers with no certain prospect of the resultant produce finding a profitable market. The owners of the farm were therefore unable to find a tenant for the farm, at any rent, which gives a fair guide as to the condition of the soil. My mother and brothers bravely stepped in and took on the farm, and transformed it. Losses followed for a few years while the harmful effect of heavy doses of chemicals was being experienced, but the land has now been built up to a state of fertility unequalled in the district. After the 1950 harvest (which was the worst in living memory) I had a letter from one of my brothers saying, ‘We have just harvested the heaviest crops ever remembered in this district, over the whole 300 acres of the farm, without an ounce of tillage’ (the North Country word for artificial fertilizers). And such results were achieved by the use of pigs, supported by the organic methods described in the rest of this book.

Tackling a field of the farm at a time, for large areas had gone back to rough grassland infested with weeds, pigs were used for every operation of reclamation, except the actual sowing of seed and levelling the ground with disc harrows.

Starting with a field in its rough state, large numbers of pigs of all ages were turned into the field and folded over it. Where there was good hedge shelter no other shelter was provided, but where the hedges were bare, rough timber and galvanized sheeting shelters were provided for sows with young litters. The Essex pigs which my brothers use seem, however, to prefer the hedge bottom to the sheds, even for farrowing.

The pigs are allowed a minimum of food, for this reason: if a large number of store pigs is available they are preferred to sows or gilts close to or just after farrowing. They then find most of their keep from the grass, weeds and roots of all kinds which they dig out as the whole field is thoroughly and completely turned over. Coarse roots of weeds, which are extremely difficult to eradicate on this rough land by any other means, are dug up by the pigs to provide food and at the same time they clean the land more effectively than is possible with a machine. Labour for attending to the pigs is reduced to the very minimum because, at the most, the pigs receive only one small feed daily, and this is raw potatoes or grain.

If the number of available pigs is limited, then folding may be resorted to, in order to ensure thorough turning of every square foot. My brothers have turned pigs on to fields as thickly as 100 to the acre in carrying out this reclamation work, but if the herd of pigs is not big enough to allow so many, the concentration may be varied by means of a fold or electric fence. If pigs of various sizes are used, two strands of electrified wire are needed, as the bigger pigs soon learn to go over the electrified single strand and the smaller pigs may go under. I have even seen a sow lying, feeding her litter, on an electrified fence which had been erected too near the ground.

When the field is completely turned over and well cultivated by the pigs, they move on to start ‘ploughing’ another field, and the first field is levelled and a rough seed-bed prepared with the disc harrows. Thousand-headed kale is then broadcast over the field.

When the kale has grown it provides all the food for another batch of pigs, which are again turned loose on the field or folded over sections of it. Again, if the herd is big enough to avoid the work of moving folds in order to concentrate a large number on a small area, the amount of labour needed to look after the pigs is no more than a walk around to inspect the pigs once daily. The kale is grazed by the pigs at a young leafy stage and they clear the whole crop down to the ground, leaving at the most only small stumps.

Then the disc harrows go in again, and once or twice over the field with disc harrows prepares a seed-bed ready for sowing wheat. Thick concentrations of pigs twice over the field and the consuming on the field of weeds, weed roots, and then the kale, have left a good covering of dung, lightly trodden in by the pigs and then incorporated into the topsoil by the disc harrows. On the poorest land, following this double dressing of pig manure, part of which has advanced in its decomposition, good crops of wheat have always been harvested. Even better results are obtained when fattening or breeding pigs are used to graze the kale, and are given additional feeding in the form of pig meal or cubes.

I have criticized the plough in various ways, mainly for its wastefulness of time, power and labour. But this demonstration of ‘ploughs’ which need neither petrol, nor oats, nor hardly any human time or labour in order to turn the turf, and which in the process of this powerless ploughing, spread fertility over the and soil—produce pork and bacon as a by-product—leaves at least one type of plough for which I have nothing but admiration.

Learn more about Fertility Farming here.

Add Fertility Farming to my cart.

About the Author:

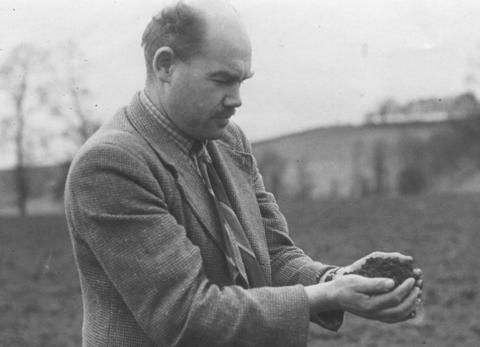

Frank Newman Turner was a visionary. He founded The Farmer, the first organic quarterly magazine “published and edited from the farm,” won the Great Comfrey Race, initiated by Lawrence D. Hills in 1953, was a founder member of the Soil Association, and became the first president of the Henry Doubleday Research Association (HDRA), now the world’s largest organic horticultural association. He later became a leading medical herbalist and naturopath and published magazines promoting natural health care and organic principles.

More By This Author:

Herdsmanship, an in-depth look at the cornerstones of cattle longevity, which could be the key to success in breeding and reproduction in cattle.

Cure Your Own Cattle, a how-to guide for holistic and natural cattle care.

Also be sure to check out Newman Turner’s Classics Collection, featuring all four of his timeless books.

Similar Titles of Interest:

- Grass, The Forgiveness of Nature, by Charles Walters

- Albrecht on Pastures (Vol VI), by William Albrecht

- Management-Intensive Grazing, by Jim Gerrish